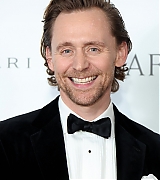

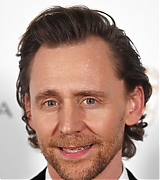

Tom is featured on the June 2016 issue of ESQUIRE MAGAZINE, and our gallery has been updated with a new photoshoot. You can read the article below.

Photo Sessions > 2016 > Session 06

As soon as we sit down, in the far corner of the Four Seasons Hotel lounge in Beverly Hills, Tom Hiddleston spots my pages of questions on the table and thanks me. “Wow, I’m so honoured. Thank you for going to so much trouble,” he says.

I tell him I’m just doing my job but he thanks me all the same, for watching his television series and his movies and for attending that screening last week and reading all those articles in his press file, particularly the one he wrote himself for the Radio Times. When it turns out some of my questions are too personal for him to answer, he apologises. Not a mumbled apology, but a full-eye-contact, sunken-shouldered “sorry”. He’s so sorry that I’m sorry for asking. He’s also sorry that he showed up five minutes late, and that his crazy schedule means we’re stuck in this bar on a Monday evening instead of, “Oh, I don’t know, playing pool or going for a walk in the canyons in this lovely weather. So I totally appreciate you making the time to accommodate. Thank you.”

Manners this impeccable are rare in anyone, let alone an A-list celebrity. And combined with his polished, plummy accent, the rich timbre to his voice, and that winning smile — by turns delighted, boyish and, yes, apologetic — the effect is so extreme as to be a parody of English charm. Only it’s not a parody, it’s real. Every sorry and thank you is meant in earnest. This is the thing about Hiddleston — he’s never just being polite.

Here’s what people say about him, journos and co-stars alike: that he’s a talented mimic who does a great Owen Wilson and Al Pacino. He even did Robert De Niro for Robert De Niro on Graham Norton’s couch, which takes some stones. But mostly, that he has this terrific attitude, so “earnest” and “enthusiastic”, probably the biggest words in his word cloud. His manners are not the half of it. Hiddleston brings a certain energy.

Scarlett Johansson described him as “clinically enthusiastic” on the set of The Avengers. Hugh Laurie told me that on the set of The Night Manager, the highly bingeable spy series that aired earlier this year on the BBC, “Tom never stops running. Before work, after work, during work. And it adds hugely to the common tank of energy that a film crew runs on. Every time someone yawns, or scratches their arse, the crew leaks a little energy — Tom’s the one who tops it up.”

And it’s true. For two hours, we talk about class, movies, JG Ballard and politics, and Hiddleston’s energy is unflagging. He answers every question with care and intelligence. (Laurie again: “he’s much brighter than a good-looking man ought to be.”) He quotes song lyrics and whole chunks of scripts from memory. There are beers, there are snacks, it’s all flowing wonderfully. And it’s especially impressive considering he’s come here straight from a press junket for his Hank Williams biopic, I Saw the Light — six hours of repeating the same anecdotes to a cattle call of journalists. He’d be forgiven for wanting to hit the heavy bag at this point, or to lie down in a darkened room waiting for the Valium to kick in. But instead, he’s here, clear-eyed and chipper as a chipmunk, giving yet another journalist the best possible interview he can.

It doesn’t take but a few minutes in the full beam of The Hiddles, when I feel my own cynicism burn off like morning dew. And I realise the question I really need to ask here is how? How does he do it? And how can I do it, too?

No doubt, there’s plenty to keep Hiddleston chirpy these days. He seems to be everywhere at once. There’s a coveted slot in culture reserved for the elegant English gent, posh totty for the nation’s housewives — it was once the domain of Colin Firth and Hugh Grant — and now Hiddleston appears to be the heir apparent. Lately, he’s been busy fielding Bond rumours thanks to The Night Manager, but there are other projects in the air, each one starkly different to the next. There’s High-Rise, director Ben Wheatley’s brilliant rendering of the JG Ballard novel, which came out in March to tremendous reviews. Then there’s I Saw the Light for which reviews have been less tremendous — The New York Times called it “inert” — though to be fair, they tend to praise Hiddleston’s part in it, his portrayal of Williams, the alcoholic, pill-popping country singer from Alabama in the Forties, hardly a minor leap for the Eton and Cambridge-educated actor. He may yet emerge from the wreckage not just unscathed, but glowing.

And for the last 88 days, he’s been travelling the world shooting Kong: Skull Island, a reboot of the legendary tale that will be set in the Seventies. He can’t say much other than it’s a fresh take on the story which doesn’t end with a big ape on a building. But he can say it was a blast to make on account of the activity weekends in Hawaii and Australia. Go-carting with Brie Larson, anyone? Admittedly, he has spent the last couple of weeks wading through a swamp in Vietnam — “and they don’t tell you about the swamp spiders and things that can get inside your wetsuit and nestle in the warm spaces” — but there’s time to heal yet.

The next instalment of Thor starts shooting in June, so at this point in time he has a couple of months to kick back at home in London’s Chalk Farm, with his cat Bentley and his two sisters, one older and one younger, who live close by. And his fans, the Hiddlestoners — not to be confused with Cumberbitches (a word that Tom would rather not say out loud) — are likely sending ointments for that rash as we speak.

His north London life, he says, is remarkably normal. The Hiddlestoners may inundate him with teddy bears but they leave him alone in public, as do the paparazzi. Hiddleston was never one to fall out of nightclubs and there’s no girlfriend to speak of either — “still single, dude! Last of the Mohicans!” So Tom can go to his local Waitrose without a ski mask. He can pop into the pub to watch the game without having to do a bunch of selfies. And that’s exactly what he plans to do.

“I can’t wait for the European Championship,” he says. “Any sports, actually. Tennis, rugby, athletics. I get so moved. When Jessica Ennis-Hill and Mo Farah won their golds, I was weeping on the sofa.” He rubs his hands together.

The waiter arrives with his Heineken, and as he pours, Tom quickly grabs the glass to tilt it.

“Otherwise we’ll have too much head,” he says.

“How much head do you want?” the waiter asks. “I’ve had plenty of practice.”

“There,” says Tom, straightening the glass. “The perfect amount of head.” And for a moment, they look at each other, Tom’s guileless, innocent face, facing a waiter who just isn’t sure whether he’s allowed to get the joke. And Tom could milk the discomfort if he wanted. He could let the waiter go, and we could laugh about it to ourselves. But he’s just too decent for all that. To cause discomfort, to laugh at someone else’s expense — it’s not him. So, he does what he does so well. He apologises.

“If you’ll pardon the expression,” he says, and winks.

The waiter grins. “You got it.”

Things took off rather suddenly for Tom Hiddleston around 2010. He’d been a jobbing actor turning heads on the stage if not on film and TV. And then Thor came out in 2011. As Loki, the Norse god’s trickster nemesis, Hiddleston went global. Then there was The Avengers, one of the biggest movies of all time. He also worked with Steven Spielberg in War Horse as the heroic Captain Nicholls, and with Woody Allen in Midnight in Paris playing F Scott Fitzgerald. Hiddleston had arrived.

At home in England, however, his success was framed as part of a posh wave in British acting, at least among the boys. Hiddleston was in the year above Eddie Redmayne at Eton (and Prince William, too). Benedict Cumberbatch, meanwhile, went to Harrow. That they’re all peaking at a time of vast inequality in David Cameron’s Britain, might suggest a symptom of a wider problem, but in previous interviews, Hiddleston has bristled about this characterisation, calling it “socially divisive”. Not any more.

“I’ve been getting more political with age,” he says having turned 35 this year. “I understand why people bring it up. There’s a justified anger about inequality of opportunity. People feel that spheres of influence, like politics and the arts, have become the preserve of a privileged few. I do think the debate can become unnecessarily prejudicial when individuals are singled out. I’ve known Eddie since 14 and I’ve never seen anyone work so hard. But actors who didn’t come from privately educated backgrounds, like Julie Walters and David Morrissey have said, ‘if I was an actor now, I wouldn’t make it.’ The grants aren’t there. When I went to college, Rada (The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) cost £3,300 for three years. Now it’s £30,000. That needs to change.”

He’s too diplomatic to pick sides, red or blue. But he did make High-Rise, a scabrous satire about the class system in England. He was the first actor to sign up. “I could see that in its DNA, it was political, and it was time to turn my face to the wind of that,” he says. “I’m inspired by something Alan Rickman said: ‘if you want to know who I am, it’s all in the work’.”

The film is merciless about the rich who live on the upper floors of the high-rise building, fretting about cocktail onions while civilisation collapses all around them. Hiddleston’s character, Dr Robert Laing, is a physiologist, caught between the upper and lower classes who are in open conflict.

“‘The building is a diseased body,’” says Hiddleston, quoting from memory. “‘The lights are like neurons in a brain, the elevators are like pistons in the chambers of the heart.’ He was so prescient, Ballard. The book talks about how the residents shoot these orgiastic parties and project them against the wall for their neighbours. And that’s the beginning of social media. He saw it all coming.”

Certainly Hiddleston’s accent and manners might suggest he hails from the upper floors, as it were, but in fact, his story is one of middle class striving. He was not to the manor born. His grandfather was a shipyard worker in Glasgow, whose son, Tom’s father, went on to run his own biotech company in Oxford in the Nineties. Tom’s mother Diana was an arts administrator, and between them they decided to give their children the best education possible, even as their marriage was falling apart. Tom was sent to Eton at 13, in the year of their divorce. In the emotional tumult that followed, he sought sanctuary in the drama department.

“As a teenager, you’re developing these more sophisticated feelings and attitudes about the world, but you don’t have the language to express them,” he says. “Plays gave me the articulacy to express what I was thinking.”

The divorce made him “more compassionate”, he says, but he won’t elaborate. It’s difficult territory. “My family is so beyond it all now, I’m sorry, dude,” he says. And he really is. “But also, I don’t want to mythologise the narrative either. Events in anyone’s life become these coat hangers on which you can hang your identity, and I’m wary of reinforcing the infrastructure of those things. It’s only retrospectively that you join the dots up. Life is so much more accidental than any of us like to imagine.”

Here’s an accident that shaped his life, for example. In the first year of his Classics degree at Cambridge, he starred in a production of A Streetcar Named Desire. He played Mitch — not the Marlon Brando character in the 1951 film adaptation, but the Karl Malden character who’s going through a mid-life crisis. Though he was a first-year, the rest of the cast were about to graduate, so they invited agents along, and the following week, Hiddleston received a call: would he like a part in an ITV production of Nicholas Nickleby?

“I got my agent, Lorraine Hamilton, who also represented Hugh Laurie, Emma Thompson and Tilda Swinton, a whole slew of Cambridge actors. And I wonder, if I hadn’t been spotted in that production, would I have had the courage to be an actor? I don’t know,” he says. “All I know is that having an agent when I left college meant I was definitely going to try. And I had saved enough money from my acting jobs to pay my way through Rada.”

Life isn’t planned out, that’s what he’s telling me. Years later, in 2008, there was another major milestone in his career, again built on chance. He’d been offered a play in London where he was enjoying a steady stream of theatrical work, but he turned it down to come to LA on a whim. He was curious.

“I thought, ‘I might not do this forever, so I want to have a little walk around the horizon so that I’ve seen all the little pockets of it,’” he says, walking his fingers around the table. “It was the best thing I could have done. Even though I turned down employment for unemployment, earning money for spending it, and every job I auditioned for I didn’t get. All except one. Right at the end, I auditioned for Thor. Massive game-changer.”

We know what happened next: he came, he Thor, he conquered. And the moral of the story is..? “When people say, ‘I shouldn’t say yes to that opportunity because I’ve made all these plans’ — what if you don’t attach so much significance to it and just turn up? Many of the most interesting things in my life have come about because I’ve said, ‘OK, I’ll try it.’”

He may be on the precipice of an adventure right now, of course, with the whole Bond business. It’s time we addressed it. Everyone else is. “No, no, of course,” he says. “It’s one of our favourite national conversations. It’s up there with ‘when is the England national side going to live up to its potential?’ and, ‘who’s going to win X Factor?’”

This is the schtick he trots out on chat shows. It’s his way of talking about it without talking about it. But however much he downplays his chances, the fact is he’s a serious contender. Of course he is; he’s spent the last year as Jonathan Pine on The Night Manager, effectively auditioning for the role.

“It is similar,” says Hiddleston. “He’s a British spy, with a military history, he’s a solitary figure, heroic, he’s in a tight spot…”

There’s a Moneypenny. He wears fancy suits. He beds blondes.

“All true!”

So, would your Bond be like Pine?

“I can’t, I… it’s very flattering but…” This always happens. He has no choice, really. He tells me how “sensational” Daniel Craig is, how his favourite movie is From Russia with Love. But he can’t wait to skip off the topic to something more meta, less personal. In fact, he’d sooner talk about why Bond is such a national obsession: “I think it’s because he represents an archetype. There’s this idea of British strength which doesn’t draw attention to itself but gets the job done. That’s our brand. We know it’s inelegant to blow your own trumpet and impolite to show how much you care, and yet we expect you to win! You don’t find it in France or Spain. Captain America is dressed in the American flag — the heroism is so much more overt. But Bond is debonair, detached, good humoured, well mannered, efficient, charming…”

And with every adjective it’s hard not to notice just how well they all apply to him. One might argue that after Daniel Craig’s brawny Bond, Hiddleston would seem a bit boyish and slim-shouldered. A preppy Bond with the body of a salsa dancer. Perhaps it’s time. But the core duality of 007 — suave and deadly — is firmly in Hiddleston’s wheelhouse. He does well with characters who present a charming front but conceal a darker, more complex interior. There’s Jonathan Pine, of course. And Laing in High-Rise, a dapper scientist who ends up killing and eating a dog. In Crimson Peak, by director Guillermo Del Toro, Hiddleston’s character Thomas Sharpe is a dashing baronet who turns out to be a murderer.

“I’m fascinated by characters like that,” he says. “Because it’s so universal. We put our best foot forward, we’re optimistic and engaging but that often masks a more turbulent private life. I think that’s true of everyone that I’ve ever met.”

And you too?

“Absolutely. It’s what makes people interesting, that tension. We’re all frail, as Angelo says in Measure for Measure. We are all consistently inconsistent.”

To illustrate life’s frailty and its accidental nature — something of a theme, this evening — he tells me about the time he saw a guy get chopped up on a slab. He was preparing for a scene in High-Rise where Laing cuts open a man’s skull. So naturally, Hiddleston did his homework. He’s known for taking his research seriously, a vestige from Eton. For Thor, he learned capoeira. For The Night Manager, he shadowed a night manager. And for I Saw the Light, in order to achieve the gaunt addict’s frame of Hank Williams, his co-star Elizabeth Olsen says “he ran 10 miles and cycled 25 miles a day, and all he ate was peanuts and salad.”

So it surprised no one when Hiddleston contacted a forensic pathologist in Nottingham and watched him perform a full autopsy. The body belonged to a young boxer who’d died in the ring. His brain was removed, the full nine. “It was a very, very tough experience,” Hiddleston says. But the reason he brings it up is something the pathologist told him afterwards. “He said the symptoms of behavioural dysfunction cannot be physically found in the brain. So, if you’re depressed or a schizophrenic or whatever, you can’t open up the brain and see it. It’s all just chemicals and nurture. Isn’t that fascinating?”

What’s fascinating for me is Hiddleston’s enthusiasm for this fact, for his job and for life in general. I’d happily look inside his brain, if it would show me where that enthusiasm comes from, that unassailable positivity. It’s easy to assume, as some have, that it gushes from an endless well; that perhaps he’s just built that way, happier than thou, and success has come rather easily. But it’s about as true as his alleged silver spoon upbringing.

“Enthusiasm can be dismissed as rather Tiggerish,” says Kenneth Branagh. “Tom isn’t that at all. He’s passionate about ideas and art, and actually I think it’s a blessing he’s not cursed with that kind of enforced sense of ‘cool’ that requires him to be a bit under-impressed, almost as a badge of honour.”

Branagh is a longtime friend of Hiddleston’s: he hired him on his detective series Wallander, then for the Chekhov play Ivanov staged at Wyndham’s Theatre, London, and ultimately on Thor, directed by Branagh. Along the way, he has witnessed some cracks in the armour. During Thor, Branagh recalls the young actor as “a bit scared and vulnerable, and at times pretty lonely. I think he withstood isolation pangs that might have thrown some people. But what I admire about Tom is he’s not trying to present the idea that a tortured individual lives alongside this gilded youth. He has a lot of the personal challenges that most people have, but he doesn’t look for sympathy by trying to convince people that there’s trouble in the kingdom.”

When I ask Tom where the shade might be in a life that seems to exude sunshine, all he says is that he has scars like anyone else, which he regretfully can’t talk about. Partly because he’s been working with Unicef lately on a documentary about rehabilitating child soldiers in Sudan. “So really, who gives a shit about my middle-class woes!”

But there are clues. In the novel of The Night Manager, Pine is described — here Hiddleston quotes — as “a perpetual escapee from emotional entanglement, a collector of other people’s languages, a self-exiled creature of the night, and a sailor without a destination. I read that to my sisters and they said, ‘It’s you!’”

And on the set of The Avengers, Hiddleston asked Mark Ruffalo the same kind of question I’m asking him now. “I said to him, ‘you have such a sunny disposition!’ And he does. He’s such a nice man, the rumours are true. And he said, ‘the bigger the front, the bigger the back, man!’ And he gave me this look like, ‘you know what I mean.’ And I think that’s true of me, too.”

The truth about Hiddleston’s bushy-tailed enthusiasm is that it’s neither forced nor easy. “It’s a choice,” he says. “Not a natural disposition.” It’s how he sees the world. Branagh sees it as a piece of “Tom’s intuition about the brevity of time on this planet and the responsibility to relish every moment.” But also as an aspect of his respect for other people, even journalists on junkets.

“He’s a generous spirit,” says Elizabeth Olsen. “As an actor, he always says, ‘you don’t think about yourself. You think about who’s in front of you. You’re trying to get them to respond.’ He’s a deeply kind person.”

“Here’s what I’ll say,” Hiddleston tells me, as another round of beers arrive. “I believe that nothing is certain and fixed, so you have to make the best efforts to treasure things, and not fall into the trap of letting things be destroyed. Because they can be.”

Bond could do worse.

Welcome to Tom Hiddleston Online a fansite for the actor mostly know for his role in Marvel's Cinematic Universe Loki. You might also know him for his role in theater plays such as Coriolanus and Betrayal, and other films and series such as The Night Manager, War Horse, Kong: Skull Island, Crimson Peak, Only Lovers Left Alive and many more. Tom Hiddleston will be seen next on Disney's series Loki and Apple TV The Essex Serpent.

I hope you enjoy you stay and have fun!

Annie

Welcome to Tom Hiddleston Online a fansite for the actor mostly know for his role in Marvel's Cinematic Universe Loki. You might also know him for his role in theater plays such as Coriolanus and Betrayal, and other films and series such as The Night Manager, War Horse, Kong: Skull Island, Crimson Peak, Only Lovers Left Alive and many more. Tom Hiddleston will be seen next on Disney's series Loki and Apple TV The Essex Serpent.

I hope you enjoy you stay and have fun!

Annie